Just last week having played Chants of Sennaar, I was discussing it with a colleague, who highly recommended I check out Return of the Obra Dinn next.

The game by Lucas Pope – the mind behind Papers Please – intrigued me in its very unique visuals and the similarity to the aforementioned title: a deduction-style puzzle game where you play as an investigator uncovering the tragedies surrounding a ship meant to sail to the far east, but returned to its country of origin inadvertently.

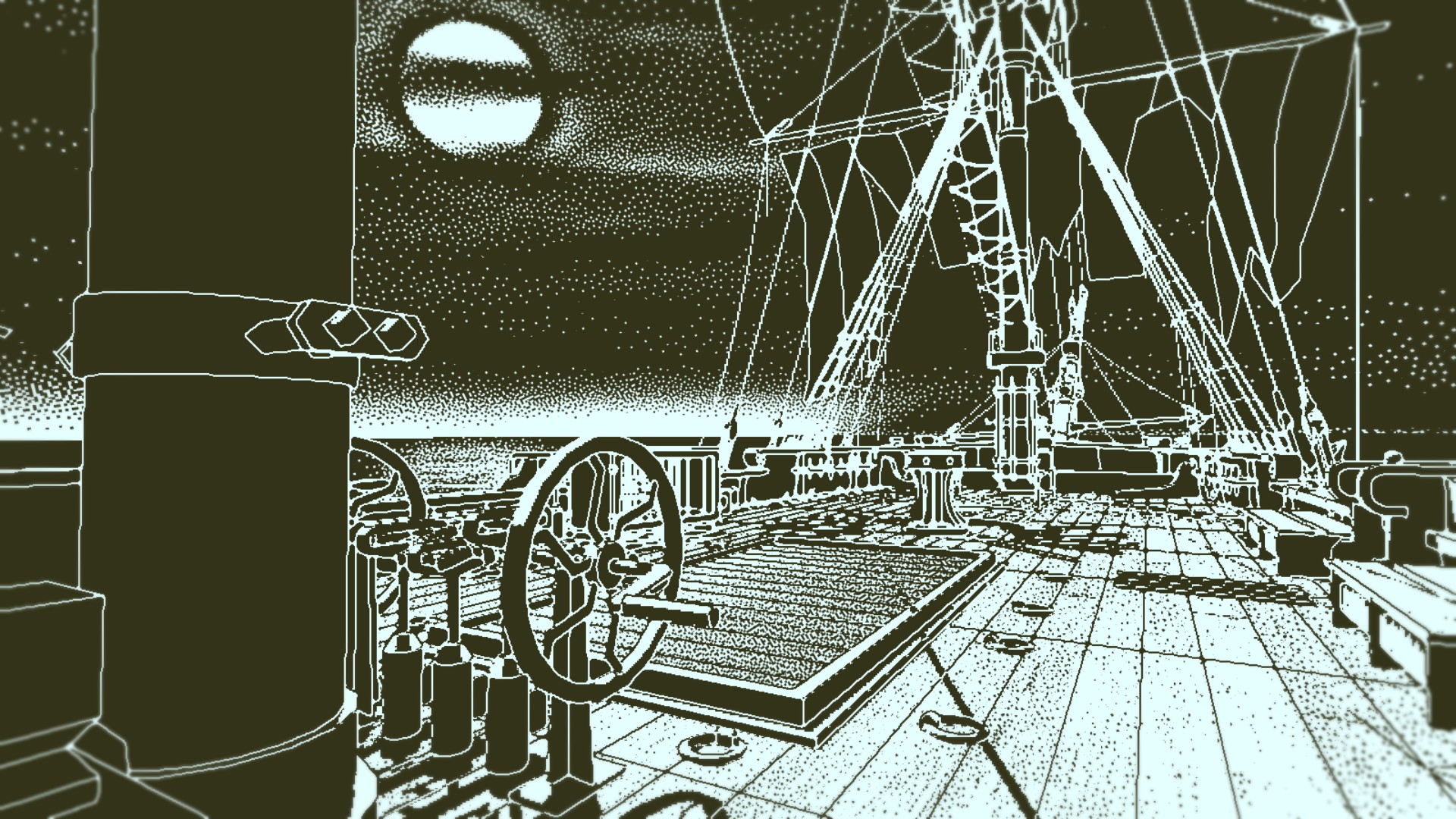

The attention to detail is exquisite, and the ambiance is set from the get-go. This becomes immediately clear by the audio effects and voice acting, meant to transport you to the mood of a 18th century boat in a far coast in the British coast.

Spoiler

The attention to detail can be verified by starting the game anew, only to realize the investigator’s voice actor changes between save slots.

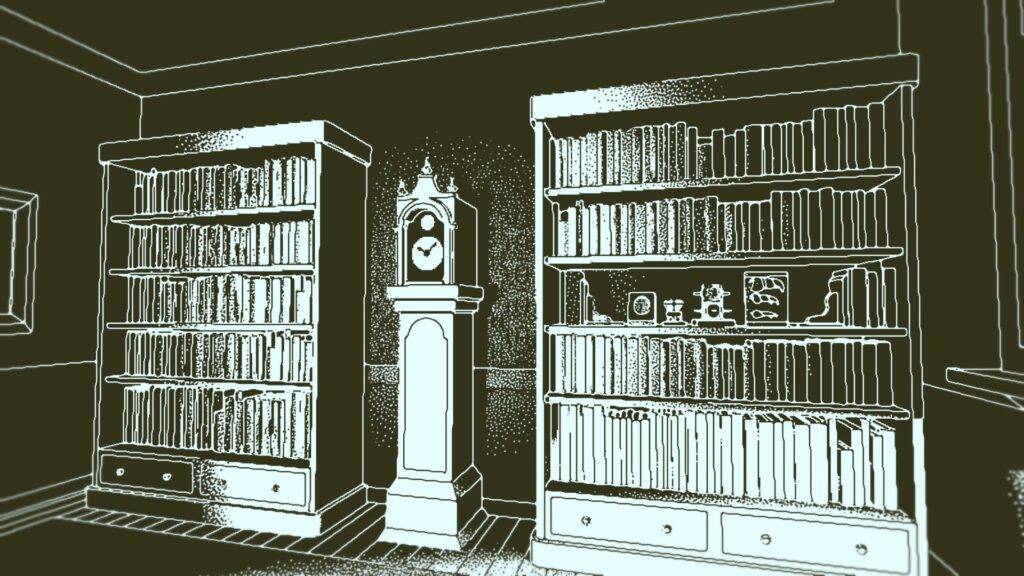

Setting foot on the boat, you might peruse around, but you shall invariably come upon a corpse – nothing but flesh and bones. Being called back by the ferryman, you get presented with your investigative tools: a notebook, and a odd pocket-watch ominously inscribed with:

Memento mori – Remember death

Returning to the corpse, it becomes clearer what the core functionality of the game is: the pocket-watch allows you to traverse in time to the very last moments of a person, so long as you point it towards their remains.

From there, it becomes even clearer how important the audio design is in this game: the pocket-watch gives you but a still-frame of the person’s death, all of the acting happens through audio-queues.

That still-frame, however, can be navigated, and in doing so you may notice people that were around, sometimes even implicated, in someone’s death.

In doing so, we unfold the events of this tragic voyage more and more. Tasked with identifying the outcome of each of the 60 people onboard when the ship set sail, we must make use of every tool at our disposal: most often than not, identifying someone and their cause of death can only be done by thoroughly analyzing their behavior, who they interact with and even their garment.

Spoiler

Something that really struck me as ingenious was how we’re able to identify each of the four Chinese top-men.

I was stuck on that for quite a while: how can I name them if no one ever addresses them, they all have the same role and nationality?

Up to that point, most of my deductions were either a direct result of mementos, or by analyzing the ship’s hierarchy.

That was until I realized that, in their first scene, they are all sleeping in numbered tents, and that each had a different pair of shoes.

The core mechanic of using the notebook to connect all the dots is satisfying, and clearly has had some influence in the execution of Chants of Sennaar. Moving about the pages, analyzing connections and events, jumping back and forth, is something that you do so often, that by the end becomes almost second nature.

That, to an extent, is the source of my only negative experience from the game, if at all: the music – always well-crafted, with choruses in violins and organs – always would get dimmed and cut when we’re zooming into people and opening the notebook in a memento scene. That, to me, broke the flow state established by the voice-acting and the music.

In any case, the story unravels so, with you as the investigator searching for remains around the ship, navigating through time and taking notes and, as it goes on, demonstrating to be more and more outlandish, with a myriad of mystic twists and turns that ultimately lead to a satisfying result.

This game well deserves the praise it receives. It demonstrates the importance of execution and sticking to what you’re trying to be towards a great story. I cannot recommend it enough.

Leave a Reply